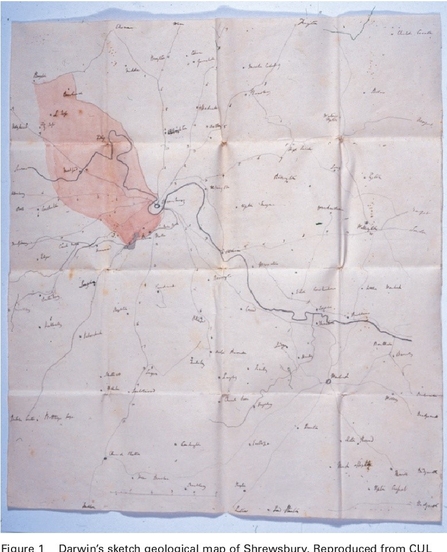

In Shropshire, we have evidence from eleven of the thirteen recognised geological periods here, more than anywhere else in the world, and the county hosted many of the earliest explorations into geology as a science.

Growing up in Shrewsbury, the young Darwin was an avid collector, and fascinated by pebbles – he wanted to know something about every pebble in front of the hall door.