The Marches Mosses are Fenn’s, Whixall & Bettisfield Mosses National Nature Reserves and Wem Moss Nature Reserve in North Shropshire. Collectively they are the third largest area of lowland raised peatbog in the UK.

This is one the rarest habitats on earth – over 96% have been destroyed, yet they play a vital role in sorting carbon and reducing the climate crisis. Lowland raised peatbogs soak up millions of tonnes of rainwater and also play a role in flood prevention.

Shropshire Wildlife Trust, Natural England and Natural Resources Wales have been working to restore 665 hectares of the Marches Mosses during the 5 year project. This is in addition to the huge areas which have been improved during the Meres and Mosses Project, which ran prior to the Boglife Project.

The restoration of this sensitive habitat originally began in the 1990s, when the collective sites became recognised for their international importance, but had been damaged by decades of commercial peat cutting. The Mosses had been heavily drained and no longer functioned as efficiently as a sponge- holding rain water and reducing the flow of water into surrounding catchment areas.

Raft spider (c) Vicky Nall

Large areas had dried out and the bog-specialist plants, such as sundews, sphagnums, white-faced darter dragonflies and raft spiders had reduced dramatically in number. The cutting of peat that had developed over millennia, also released huge amounts of carbon into the atmosphere and reduced the amount of carbon that the sites could store. Natural England have managed Fenn's, Whixall and and Bettisfield Mosses since commercial peat cutting ended.

The Boglife Project website contains lots of information about the Mosses area, places to visit and what to see when you are there.

Why peatland is an important habitat

The Marches Mosses are beautiful, tranquil places that are full of wildlife and intriguing to visit. They are also vital for the health of the planet as we try to lessen the impact of carbon emissions on climate change.

- Peatland is 90% water. Peat bogs work to slow the flow of rainfall through the landscape, thus helping to prevent local flooding.

- Global peatlands contain at least 550 gigatonnes of carbon—more than twice the carbon stored in all the forests in the world.

- Peat forms at a very slow rate – only 1mm per year - so any loss of peat, including for garden compost, takes hundreds of years to rebuild.

- Peatlands cover just 3% of the world’s surface, yet hold nearly 30% of soil carbon, keeping the carbon out of the earth’s atmosphere.

- Peat that is drained and therefore dries out releases stored carbon into the earth’s atmosphere, thus adding to the climate crisis.

- The cold, waterlogged, acidic conditions of peatlands create an ideal habitat for a unique set of flora and fauna to thrive.

Read more about how peatlands help tackle to climate crisis here

How do peatlands help flood prevention?

The primary objective of BogLIFE project on the Marches Mosses has been to restore the peat over the 2,500 acres of this valuable peatland. By doing so, the project team are also helping to “slow the flow” of rainwater that, previously, was allowed to escape the Moss, draining into the river system downstream.

Peat is 90% water, all of it from rainfall; peatlands typically occur where there is high rainfall – 700-1200mm per year. With climate change experts forecasting that UK winters will get wetter as the climate crisis affects our weather, holding the water on the Mosses is an important part of flood management.

The restoration work by the BogLIFE project has included moving drains away from the Mosses in ways that protect the surrounding areas, as well as blocking up a myriad of smaller drains that used to criss-cross the Mosses.

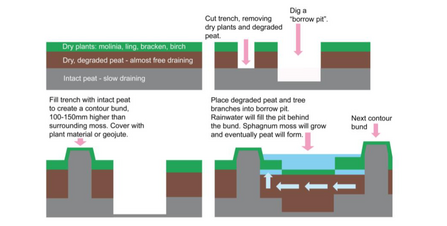

Restoration has focused on creating bunding throughout the Mosses that capture the rainwater. These are ridges, about a metre high, that the team create in large squares, often 30 metres square. The diagram, below, shows how the bunds are made.

The restoration work has also had a positive impact on the biodiversity on the Mosses. In this video, Steve Dobbin of the BogLIFE project talks about how snipe have returned to the Mosses and shows how bunds are created: https://youtu.be/0k5NsvHOeTY

Diagram to demonstrate how bunding is created

Wildlife at the Marches Mosses

The Marches Mosses is a rare habitat that’s home to incredible bio-diversity. From birds overhead to the smallest invertebrate on the peat, there are plants and animals that are adapted to the high acidic, low nutrient nature of the peat bog.

Some of the key species include:

Sphagnum moss (c) Vicky Nall

Sphagnum moss is the key plant in the bog., storing up to 20 times its weight in water!

Adder (c) Jon Hawkins

Adders bask in the sun on dried bracken along the edges of the Moss.

Raft spider (c) Vicky Nall

Among many invertebrates on the Mosses, the most famous is the raft spider. Raft spiders are hard to spot, but worth the wait to watch for them in a bit of open water.

Hobby (c) Stephen Barlow

Watch for the distinctive flight pattern of the hobby as it darts over the peat in search of its dinner.

White faced darter (male) (c) Vicky Nall

The White faced darter is a specialist of lowland raised peatbog and therefore only found at certain sites in the UK. Look for them along trails and at bog pools.